We're building AI like we built airplanes

We didn't conquer the skies by flapping our arms. We did it by understanding flight on its own terms. The same applies to AI: real progress comes not from mimicking human minds, but from designing systems that play to the strengths of our machines.

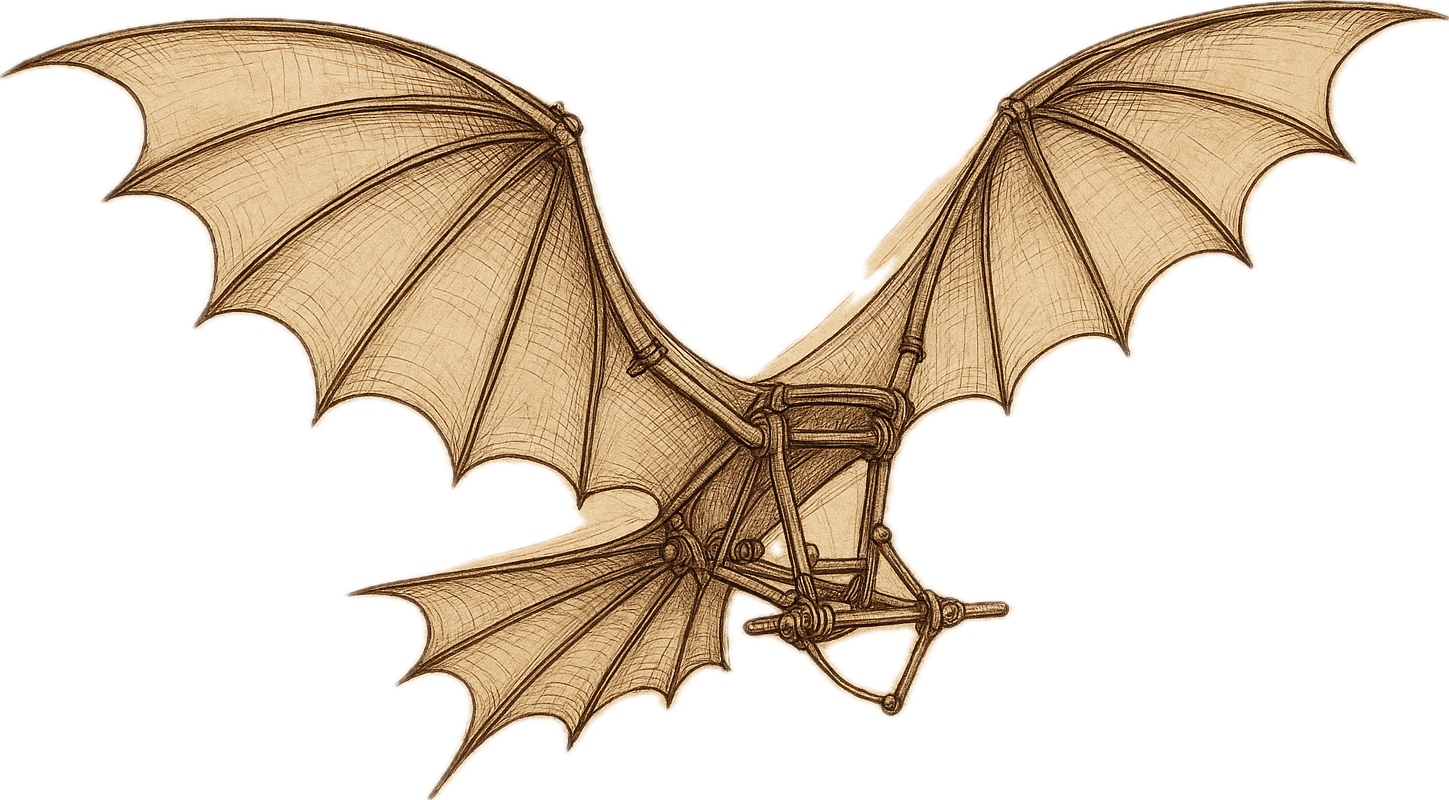

The glorious, misguided attempts at flying like a bird

Humanity has always dreamed of flying, and for most of history, we've gone about it in the most tragically wrong ways.

Before the Wright brothers nailed powered flight in 1903, people tried all sorts of wild, creative, and mostly catastrophic ways to get airborne:

Leonardo da Vinci, back in the 15th century, sketched out ornithopters (machines with flapping wings), parachutes, and a helicopter-like “aerial screw.” Gorgeous designs, but physics had other plans. Most were impossible to power with mere human muscle.

Then came the "Tower Jumpers." For centuries, eager pioneers strapped makeshift wings to their arms and launched themselves off tall buildings. Spoiler: these flights usually ended with broken bones. The flaw? Trying to fly like birds without grasping things like lift, drag, and why gravity always wins.

Looking back, the mistake is clear: they focused on looking like birds rather than understanding how birds fly. And they seriously underestimated the raw power it takes to keep something human-sized in the air.

If at first you don't succeed, flap harder (the ornithopter era of AI?)

Early AI wasn't so different.

Take ELIZA, a chatbot from the 1960s. It gave the illusion of understanding by matching patterns and swapping out text based on hand-coded scripts. It sounded smart. Until it didn't.

Expert Systems, the General Problem Solver, and others followed similar paths. They aimed to mimic how we appear to think, rather than grappling with the complexity of what thinking really is.

Personally, I also remember my early years learning programming in an MXS Basic computer. I recall having thoughts about how big and complex an MXS Basic program had to be, in order to replicate the humand mind. And I, too, thought about it being a giant sequence of IF statements wrapped in a loop. An IF statement for every possible situation in life. It seems so silly now.

We were building digital versions of ourselves based on how we imagine our minds work… which, it turns out, is kind of a hot mess. The results felt clever on the surface but lacked depth.

Winter is coming

Spoiler alert: those systems didn't delive on the hype. By the 1970s and through the 1980s, the AI field entered its "winter": funding dried up, interest faded, and researchers had to either pivot or perish.

Yet, some ideas survived the freeze (like neural networks) because they offered a fundamentally different way forward. The pause, painful as it was, cleared the air for better thinking.

The aerodynamic shift for AI: finding our own path

The real progress came when we stopped trying to copy the human mind like a costume and instead focused on what machines can do well. Who would've thought that matrix multiplication would be the path to AI?

Starting in the '80s and '90s, we started paying attention:

- Statistical models over symbolic rules: Because reality, it turns out, doesn't give a damn about our neat little if-then statements. Probability became our new best friend in the face of a stubbornly messy universe.

- Machine learning over hand-coded knowledge: We finally admitted we weren't smart enough to teach computers everything rule by rule. So, we got lazy (or clever?) and made them do the learning from mountains of data. Works surprisingly well.

- Neural networks rebooted: With better training methods like backpropagation, deep learning took root.

- Narrow intelligence > general intelligence: Tackling small, specific problems rather than trying to build all-knowing brains.

And eventually, it turned out that attention is all we needed 😉

The aviation parallel

It's a similar story as flight:

- Fixed wings beat flapping: Once we gave up on bird mimicry and embraced aerodynamics, we took off, literally.

- Function over form: The Wright brothers didn't care if it looked like a bird. They focused on what worked.

- New materials: We didn't build feathers. We built wings out of canvas, wood, and eventually metal.

- Lift and thrust separated: Birds flap for both lift and motion. Planes split those jobs, and got much better at both.

In both AI and aviation, we finally made progress when we:

- Stopped copying nature's form and started learning from its principles

- Played to our strengths instead of imitating biology

- Trusted science and data over gut feelings

The big wins didn't come from building things that looked like birds or brains, but from designing things that flew and thought in ways uniquely suited to our tools.

Think different

So, as AI continues to evolve, maybe we should stop asking "Will it ever think like us?" and start asking, "What incredible, entirely alien forms of thinking can we unlock if we stop trying to build a better human brain and instead build something... else?" The sky wasn't the limit for flight once we stopped trying to be birds. What's the 'not-a-brain' equivalent for AI that will let it truly soar?